Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems

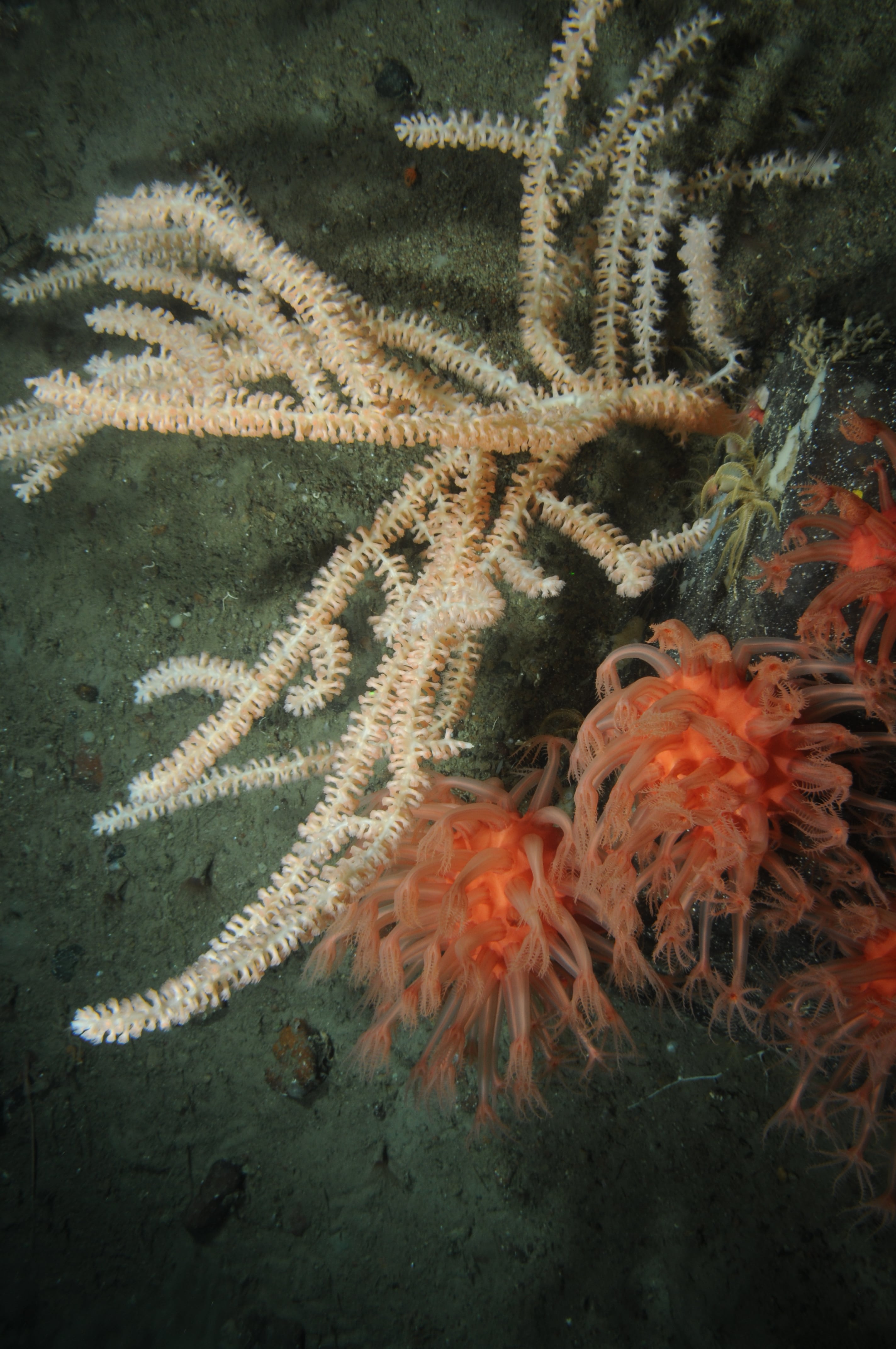

The deep-sea constitutes the largest source of species and ecosystem diversity on earth. The impacts of deep-water trawl fisheries on benthic habitats associated with seamounts, and other deep-sea environments, need to be managed. The lack of information related to marine biodiversity requires the application of the precautionary approach. Significant efforts have been made by RFMOs/As to collect relevant data and develop methodologies and tools to identify VMEs for fisheries purposes in ABNJ. The ‘FAO Guidelines for the Management of Deep-Sea Fisheries in the High Seas’ has provided assistance to States and RFMOs in the development and implementation of measures to manage deep-sea fisheries. However, further progress is still required in their implementation.

Impact of fishing gear on deep-sea biodiversity

One threat to VMEs and EBSAs in ABNJ comes from deep-sea fisheries. The impact of individual fisheries on target species and associated biodiversity is often poorly understood due to a lack of information. This, in turn, limits the ability of fisheries management measures to mitigate the impact of fisheries on biodiversity. These knowledge gaps need to be addressed in order to properly assess the impact of fisheries on VMEs, and to implement conservation and management measures. This is especially relevant when taking into account the vulnerability of deep-sea habitats to physical damage and their prolonged recovery time. The limited knowledge of deep-sea habitats and ecosystems presents a further challenge.

Understanding the risks and threats

A better understanding of the specific impacts of fishing gear on marine biodiversity is also necessary to assess the risks and threats associated with their use. In order to develop and implement conservation and management measures to protect VMEs from significant adverse impacts, a clear understanding of the risks and threats posed by fishing gear is necessary.

Where we worked

The ABNJ Deep Seas Project worked closely with RFMOs/As that have a mandate for deep-sea fisheries. The project also collaborated with other deep-seas fisheries stakeholders.

How we worked

We reviewed the processes and practices that have been developed by RFMOs with a mandate to manage deep-sea fisheries in the High Seas. The review also included measures adopted and applied by RFMO/As that reduce or prevent significant adverse impacts on VMEs. This review was undertaken in consultation with the respective regional organisations.

To improve EBSA descriptions and facilitate the development of options to avoid or mitigate threats to deep-sea biodiversity, information was gathered on the biological and ecological characteristics associated with biodiversity in the Indian Ocean and Southern Indian Ocean. The risks and threats of major types of deep-sea fishing gear on biodiversity were also analysed. Further information was compiled on connectivity for marine megafauna to understand where and how these species could be protected from the impacts of deep-sea fisheries.

The project then facilitated exchange of information between specific fisheries and biodiversity conservation efforts related to VMEs and EBSAs. As part of this, we hosted workshops to help build capacity for selected developing countries to integrate best practices for sustainable deep-sea fisheries and biodiversity into their national and regional management processes.

An economic valuation of ecosystem services for the deep-seas was also undertaken. The valuation considered services delivered by the deep-seas and ABNJ. A total economic value (TEV) framework was used to assess a wide range of goods and services delivered by the deep-sea, including: i) deep-water fish; ii) precious corals; iii) deep-water and ultra-deep-water oil; (iv) pharmaceuticals of marine origin; (v) deep-sea mineral ores; (vi) carbon sequestration; (vii) scientific research and education; and, (viii) recreation and leisure.

Key outputs & findings

Vulnerable marine ecosystems – Processes and practices in the High Seas

The review undertaken produced important knowledge, information and good practices. These are valuable for the ongoing discussions on the development of protective measures aimed to reduce significant adverse impacts on VMEs from bottom fishing activities in the High Seas. Key findings, among others, include:

- Most RFMOs/As have integrated the VME criteria and have thus expanded their data collection processes to include reporting on agreed VME indicator species;

- RFMOs/As have applied the precautionary approach and closed underwater features to fishing, such as seamounts, which were regarded as areas where VMEs are likely to occur;

- Approaches, such as productive modelling, are now used to help decide where VMEs are most likely to occur; and,

- Remotely operated unwater vehicles are considered the best way to identify VMEs, but are often expensive and time-consuming to operate. However, efforts are underway by RMFOs to gather key information that can help the identification of VMEs.

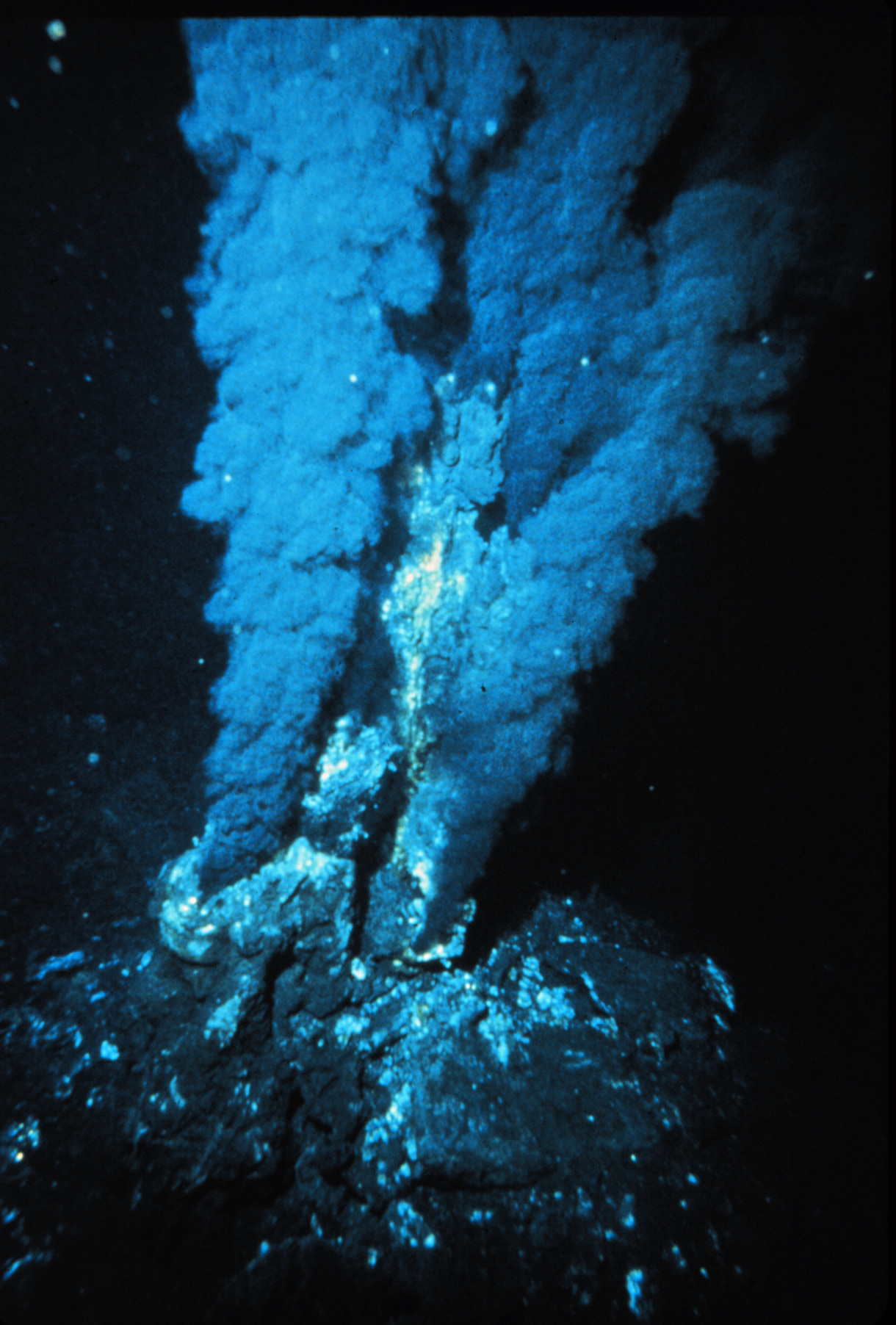

Deep-ocean climate change impacts on habitat, fish and fisheries

Changing environmental conditions have an impact on the deep ocean, deep-sea fisheries and benthic ecosystems. Rising temperatures and declining oxygen levels have already been documented at 200- 2,500 metre depths, where deep-sea fisheries take place. Temperature changes are anticipated to change the distribution of fish stocks and indicator VME species. Better monitoring will be required to provide an early warning of the impacts of climate change and to modify conservation and management measures as necessary.

Capturing ecosystem services in ABNJ

ABNJ provides a multitude of services to society, including from the fisheries sector. As part of the ABNJ Deep Seas Project, a comprehensive assessment of the value of ecosystem services in ABNJ was undertaken. A major finding of this study is that abiotic resources (oils and minerals) in the deep-sea give huge economic benefits to humans. Another important benefit is the carbon sequestration function of ABNJ. Other findings from the project include,

- Bioprospecting activities using biological material from deep-sea organisms is ongoing and will need to be fully accounted for in the future;

- Approximately 160 000 tonnes of ABNJ deep-sea fisheries are landed yearly with a value of USD 450 million. While these values are relatively low compared to global landings, deep-sea fisheries are an important contributor to livelihoods and food security;

- International carbon markets do not fully account for carbon sequestration by the ocean; and,

- Investment made for scientific research in the deep-sea is stated as nearly USD 5 billion. Yet it is thought this is figure is an underestimate due to large gaps in data of investments at the national level.